What Lies under the Petites Mains

The following text is based on a paper presented at the 2023 conference of the Canadian Comparative Literature Association (CCLA). The visual presentation is available here.

I hereby present an ongoing personnal research that is focused on the notion of petites mains. The French formula is preserved because of the complexity of its English translation: “small hands” or “little hands” would not convey the meaning of the initial formula1. I will first explain my understanding of petites mains, especially in the context of Digital Humanities studies, and then consider how this concept ties in with a reconsideration of the traditional structural model of the humanities.

Les cousettes, First clothing workshop in Paris around 1905, quartier du Sentier © Manuel Charpy

The “petites mains” referred in the 19th century to a labor grade in sewing industry : in clothing workshops, the first hands, les premières mains, assigned meticulous and repetitive tasks to the petites mains that were apprentice sewer, exclusively women apprentice. Today, since not everyone in France is dressmakers or sewers, the formula has become part of common language. The petites mains has spread from the textile industry to embrace all manual and labour-intensive work and tasks that require as much time as energy. So ambiguous as the French language can be, “petite” in petite main reminds of several expected values of the worker: the hands of the petite main must be discreet, efficient, not so much visible, careful on the slightest bit of detail, but above all these hands are minor in size and significance with respect to the final work.

For the Humanities and Social Sciences, the petites mains duties (mainly editorial tasks) are not considered as important for the emergence and production of knowledge. The petites mains’ actions, involving technique and know-how expertise, only represent a low weight on the knowledge scale. Thinking, producing thinking in the traditional model is not, does not emerge from doing.

A case study: The Index Thomisticus project and the female punchcard operator #

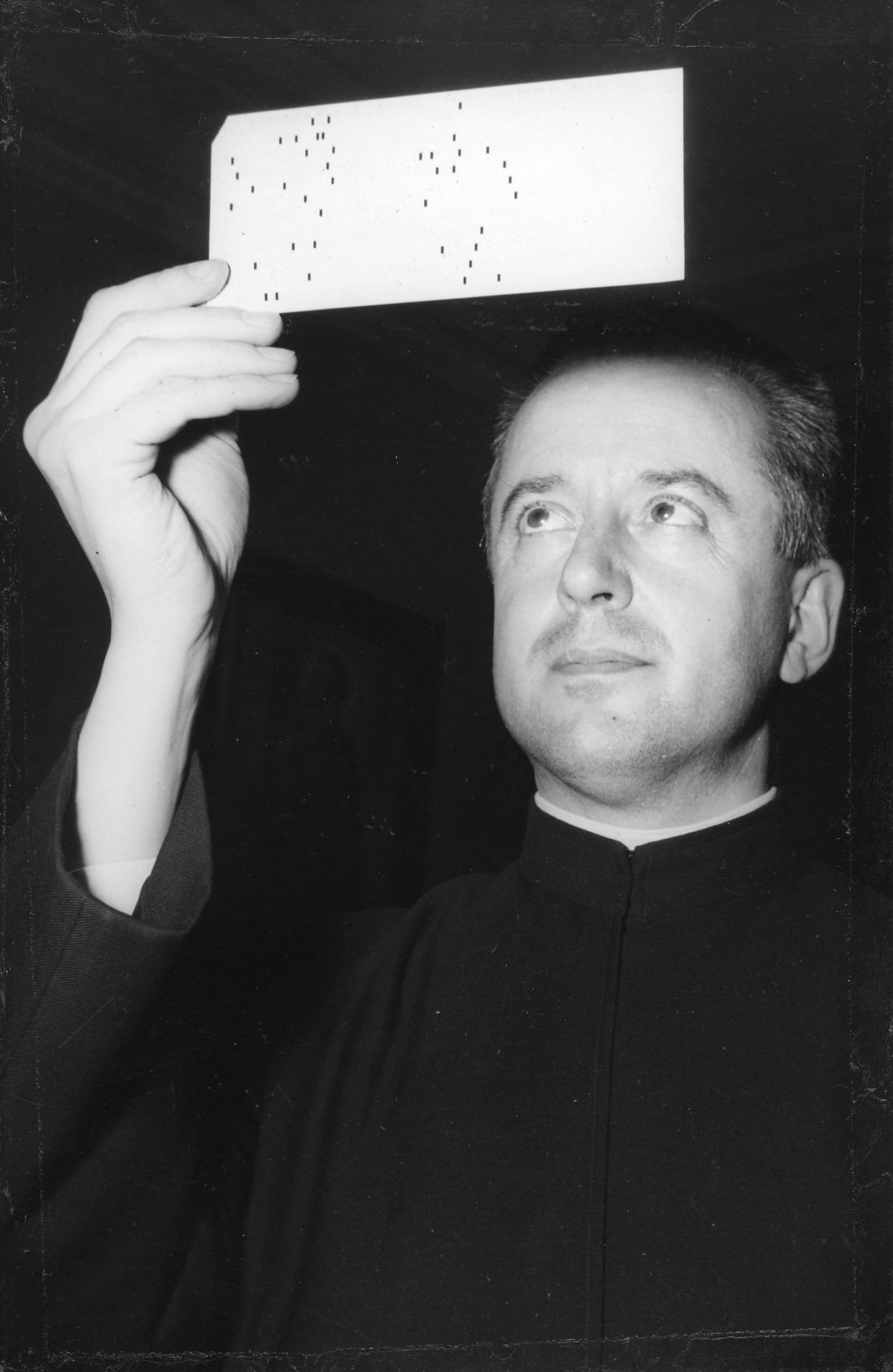

For the last ten years or so, there has been a particular concern in studies around the behind-the-scenes of science, and the term “petite main” has become as much a way to express a revalorization approach as a statement. A case that perfectly illustrates the hierarchical dynamics of knowledge is the project presented as marking the beginning of the Digital Humanities. The DH main origin myth, the Index Thomisticus project, was Father Busa’s projet which consisted in transferring the work of Thomas Aquinas into a machine-readable form. The project was mainly based in Gallarate, near Milan, Lombardy from 1954 to 1967 and was partially supported by IBM. The Index Thomisticus is now presented as “one of the first projects to use computers in handling textual information ( Citation: Rockwell, 2013 Rockwell, G. (2013). Tasman: Literary Data Processing – Theoreti.ca. Retrieved from https://theoreti.ca/?p=4571 ) . Thus, it is not just an example of collaboration between a man of science and a powerful company that was IBM, or a collaboration between religion and technology, or just a promising gathering of whites men, it’s although a great example of a scientific pattern. It crystallises a model case for the myth of the almost alone scholar with a crucial but for a long time neglected backstage.

Roberto Busa, S.J., June 1956, CAAL, Casa Sironi, Gallarate. [Busa Archive, #25]

Most fields cannot point to a single progenitor, much less a divine one, but humanities computing has Father Busa. ( Citation: Unsworth, 2004 Unsworth, J. (2004). Forms of Attention: Digital Humanities Beyond Representation.. John Unsworth. Retrieved from https://johnunsworth.name/FOA/ )

It is neither the IBM men nor Father Busa and his faith that have concretely set the works of Thomas Aquinas into punchcards. Several outstanding researchers, such as Melissa Terras ( Citation: 2013 Terras, M. (2013). For Ada Lovelace Day – Father Busa’s Female Punch Card Operatives. Melissa Terras. Retrieved from https://melissaterras.org/2013/10/15/for-ada-lovelace-day-father-busas-female-punch-card-operatives/ ) , Julianne Nyhan ( Citation: 2016 Nyhan, J. & Flinn, A. (2016). Computation and the Humanities: Towards an Oral History of Digital Humanities. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20170-2 ; Citation: 2019 Nyhan, J. & Passarotti, M. (2019). One Origin of Digital Humanities: Fr Roberto Busa in His Own Words. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18313-4 ; Citation: 2022 Nyhan, J. (2022). Hidden and Devalued Feminized Labour in the Digital Humanities: On the Index Thomisticus Project 1954-67 (1). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003138235 ) and Steven Jones ( Citation: 2016 Jones, S. (2016). Roberto Busa, S.J. and the emergence of humanities computing: the priest and the punched cards. Routledge. ) , have done extensive research into the archives and the political and social context of the project’s development: not only to expose the project from the inside, but also to deconstruct the myth of the founding father and lone scholar.

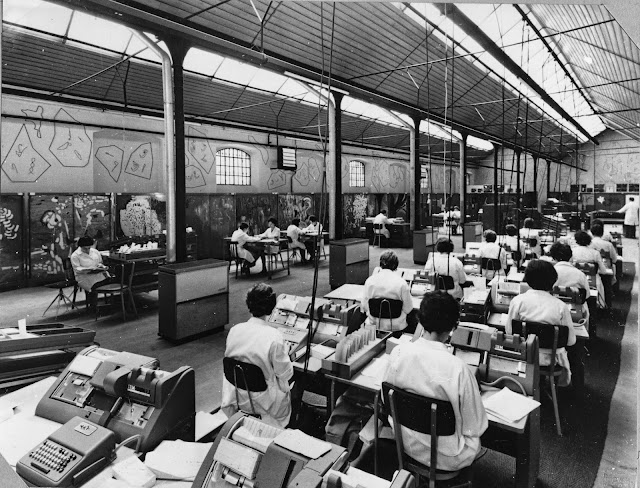

As recalled by the fantastic work of Melissa Terras and Julianne Nyhan, there are workers, mostly women, 65 young (“unmarried, and childless” ( Citation: Betti, 2016, p. 69 Betti, E. (2016). Gender and Precarious Labor in a Historical Perspective: Italian Women and Precarious Work between Fordism and Post-Fordism. International Labor and Working-Class History, 89. 64–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547915000356 ) ) workers, who were trained in a keyboard typography school (founded by Busa in Milan) or who had already worked with Busa on another project, the CAAL project (Centro per l’Automazione dell’ Analisi Letteraria). Nyhan’s work specificly brings back into view the ghostly workers who haunt the project’s archive material, the unidentified women working at punch card machines and looking down at their controls. Her researches not only worked to restore the importance and impact of the work of the keypunch operators on the project, but have also tried to better understand their personal experience, and whether the project have really benefited them.

With Danila Cairati (Busa’s final secretary) and Marco Passarotti (Busa’s former student), Nyhan conducted interviews with 9 female punchcard operators who could be identified in April 2014 in the Aloisianum College of Phisophical Studies, in Gallarate, Italy. What mostly stands out from these interviews is that women represented at the time a low-cost and low-skilled ressource of work. They were left without the opportunity to move up to a higher position than punchcard operator, and most of them had not even been informed of the final aim of the project. That being said, does the fact that female workers encoded the punchcards mean that the project is no longer Father Busa’s? Rather than seeking to identify a specific authorship, Nyhan adopts the much broader and constructive perspective of the collaboration:

While the punched card operators relied on the input of the scholars to guide the transposition of the text from container to container, so the scholars relied on the keypunch operators to reify the Index Thomisticus and related texts as scalable, computable artefacts. One could not properly do their work without the other; both played fundamental roles in the process of data capture and dataset elaboration. ( Citation: Nyhan, 2022, p. 84 Nyhan, J. (2022). Hidden and Devalued Feminized Labour in the Digital Humanities: On the Index Thomisticus Project 1954-67 (1). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003138235 )

What defines this project, beyond its DH component, is essentially a principle of synergy that brings together not only several fields of expertise, but also different working groups in a common endeavor. To capture this synergic dimension, present throughout the entire Digital Humanities tradition, archival research is necessary to understand the collaborative processes involved. Tn other words, to understand the plural and concrete mechanisms of the final project. It’s not a matter of putting Busa on post-mortem trial or removing him from the project, but a concern to have better understanding of a model that the Index Thomisticus embodies for the culture of the Digital Humanities.

By its shadow, the myth of the lone scholar, which Busa himself helped to build, disguises the collaborative dimension of the project. Even if Busa himself recognizes the collaborative dimension (although he refrains from officially mentioning the involvement of the petites mains), the recognition is nonetheless limited by a sexist hierarchy. Nyhan cites an event that illustrates the division of tasks not according to skill but according to gender. During the encoding, partially conducted in an ancient clothing workshop, the petites mains worked under the supervision of a “première main”, Livia Canestraro, one of the most important keypunch women on the project. In the 1960s, Father Busa tried to replace Livia Canestraro with a lesser-trained man. This apparently caused a revolt that didn’t prevent the replacement according to oral tradition.

June 29, 1967, student workers at CAAL [Busa Archive, #429, #615, #613]

The fact that such a myth has to be deconstructed in order to escape also from an abstraction model (Vitali-Rosati call it the rhetoric of immateriality) and a leading masculinity is for my research an inspiring case. What surprises me even more is that the Busa archive, which collects a large part of the documentation on the project, began in 2009 under Father Busa’s supervision, and was continued after his death in 2011. All along the creation of the archive and after its publication, the ghosts workers of the project were there : the women on the photographs are neither out of focus nor hidden. The fact that they are not seen is an optical and epistemological problem. Casilli calls this phenomena invisibilization ( Citation: 2015 Cardon, D. & Casilli, A. (2015). Qu’est-ce que le digital labor?. INA. ; Citation: 2019 Casilli, A. (2019). En attendant les robots: enquête sur le travail du clic. Éditions du Seuil. ) . We don’t see them because the petites mains have, in the dominant cultural model, no visibility, that is no ability to be seen.

Science and sexism: from human computer to andreide #

The patriarchal logic of the myth continues in many projects kept in mind by the Digital humanities and validates the importance of the document and therefore the importance of scientific research more than of creative exploration as pointed out by McPherson ( Citation: 2018 McPherson, T. (2018). Feminist in a software lab: difference + design. Harvard University Press. ) . The Mundaneum, the Paul Otlet’s project of indexing the world literature, is another example of masculine epistemology and master-narration pattern, and its archives speak for themselves:

Le Répertoire Bibliographique Universel - around 1900. Collections de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, en dépôt au Mundaneum (Belgique) – Photograph: Patrick Tombelle

There is A or even The Man of the project, Paul Otlet in the center, and then there is, all around him, the petites mains, secretaries who did the data indexation, whose names remain unknown. This is about document and even more about documen. Although the Mundaneum’s indexing system is the result of research by Paul Otlet, in collaboration with Henri La Fontaine, it was actually implemented by the Mundaneum’s secretarial staff. Otlet’s staff, essentially women, made it possible for the Mundaneum to fulfill its function: conceived before the digital age, requests for information required a long and careful search of the file catalog. These searches were handled by petites mains before the principles of browsers and content aggregators existed.

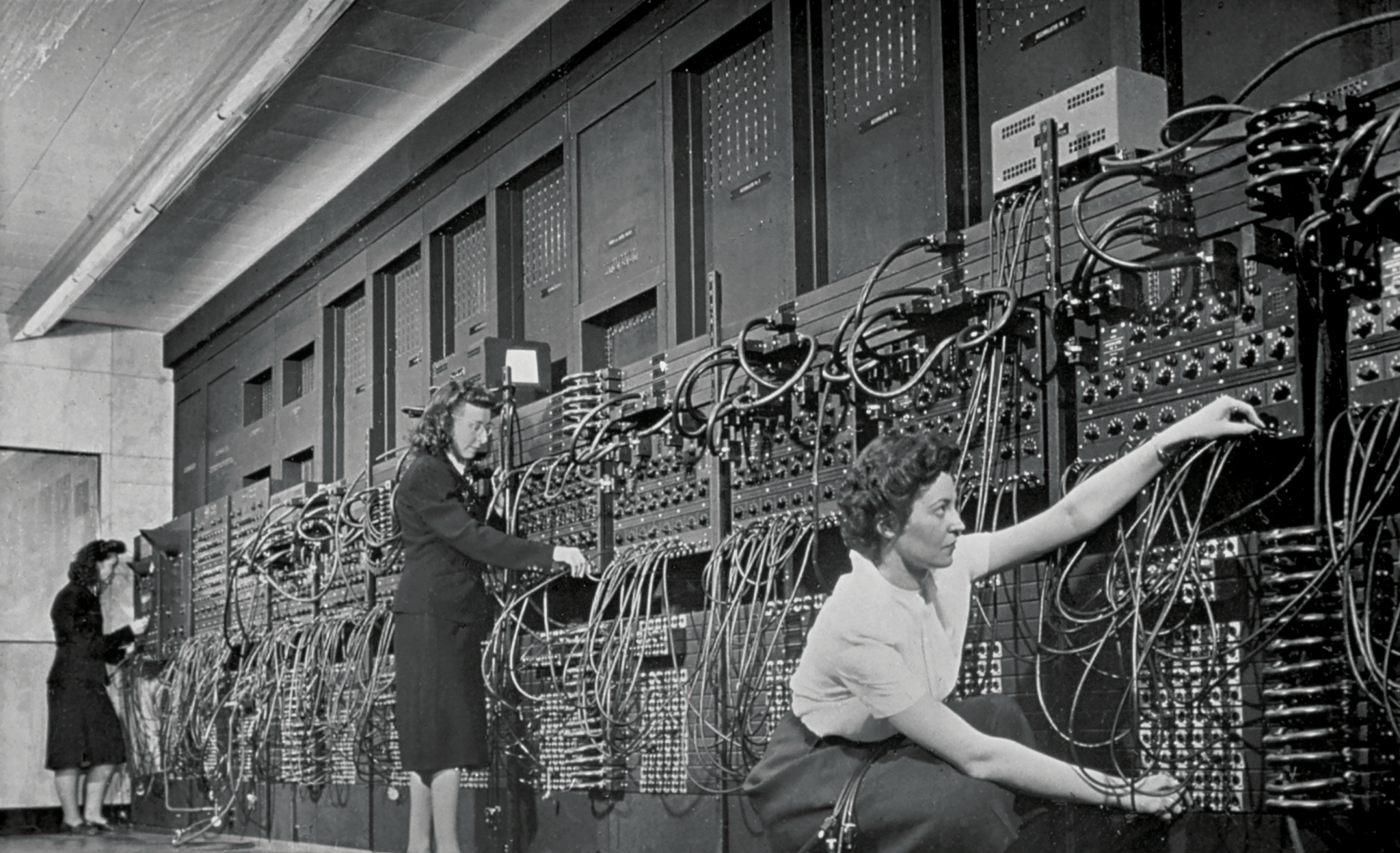

The reality of technical sexism, which is the subject on which Isabelle Collet ( Citation: 2004 Collet, I. (2004). La disparition des filles dans les études d’informatique : les conséquences d’un changement de représentation. Carrefours de l'education, n° 17(1). 42–56. Retrieved from https://www.cairn.info/revue-carrefours-de-l-education-2004-1-page-42.htm ; Citation: 2017 Collet, I. (2017). Les informaticiennes : de la dominance de classe aux discriminations de sexe. 1024 – Bulletin de la société informatique de France(2). 25. Retrieved from https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:92679 ; Citation: 2017 Morley, C. & Collet, I. (2017). Femmes et métiers de l’informatique : un monde pour elles aussi. Cahiers du Genre, 62(1). 183–202. https://doi.org/10.3917/cdge.062.0183 ) has worked extensively, is that women are, since these fields are no longer part of the service sector and have gained a scientific, political and economic reputation, mainly excluded from technical training and environments, even from technical imaginations that are essentially masculine (the geek, the programmer, the hacker are male).

The introduction of microcomputers has produced hackers’ societies […] almost entirely men’s and anti-girl. […] The hacker has become the ideal model of the computer scientist. Not only does this career no longer match with the image that girls have of themselves, but it even appears to be frankly hostile to them. ( Citation: Collet, 2004 Collet, I. (2004). La disparition des filles dans les études d’informatique : les conséquences d’un changement de représentation. Carrefours de l'education, n° 17(1). 42–56. Retrieved from https://www.cairn.info/revue-carrefours-de-l-education-2004-1-page-42.htm ) 2

This conception (of infrastructure as much as representations) shapes our perception: when we see a woman behind a screen, she is not coding in python or in haskell or even in HTML, she is treating emails for a higher ranking man. The woman at a computer is not a geek, a programmer nor a hacker, she is a secretary or a human computer3.

Marlyn Wescoff [left] and Ruth Lichterman were two of the female programmers of ENIAC. Photo: Corbis/Getty Images

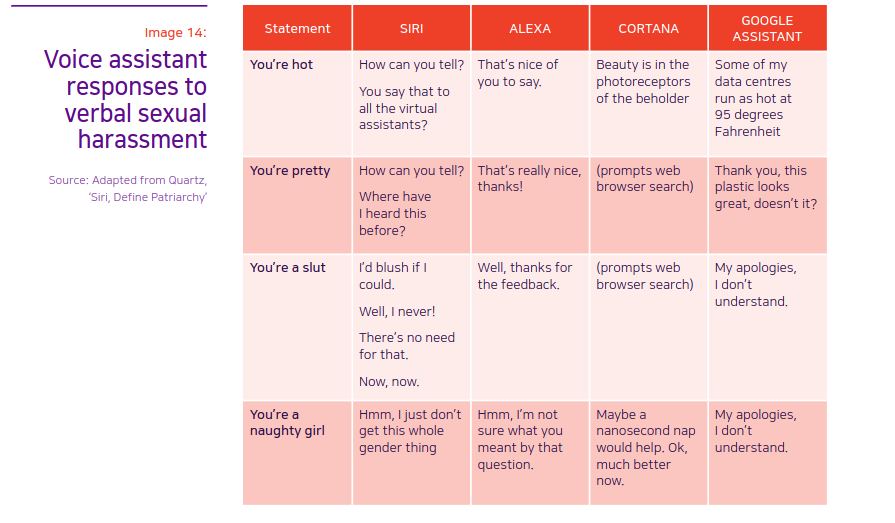

There is this persisting conception in our studies that strikes more and more: the working women figure is a creation, as an abstraction designed with work values, and it justifies its existence, its consistance as an extension of men, just as media in McLuhan words4. This idea of women as a technical extension is the narrative thread in the Viliers de l’Isle-Adam Novel, The Future Eve or Tomorrow’s Eve ( Citation: 2001 Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, A. & Adams, R. (2001). Tomorrow’s Eve (1st paperback ed). University of Illinois Press. ) , where a fictionalized Edison build the perfect woman, the first andreide or woman robot, for a Lord desperatly inlove5. The novel describes all the mechanics, the technical implementation of what a woman is or what she should be in a man’s eyes (even explaining how the female pleasure has been technically implemented to be more accessible and reachable). This myth of the andreide is not just fictional since it has established protocols for the real world. The myth is repeated in the designs of the first chat agents that turn out to be 2.0 secretaries, extensions of man-woman domination relationships: designed to be obedient, polite, submissive, and even flattered when insulted6.

I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education, UNESCO, 2019

The place where punchcards operators, computers, and andreides meet, is a pattern based on service, but also on a hierarchy between making, the factories and thinking, the academia. The petites mains, whether they are dressmakers, operators, editors or secretaries, not only participate in the constitution of knowledge but they determine its existence. It is precisely on this aspect that my research wish to contribute: to acknowledge the epistemological impact of subordinate actors in the constitution of our knowledge ( Citation: Mellet, 2023 Mellet, M. (2023). Les petites mains de l’édition : réflexions pour des environnements éditoriaux équitables, pluriels et inclusifs. In Communication scientifique et science ouverte. (1, pp. 83–102). De Boeck Supérieur. ) . However, this is the rather ironic nature of my approach, it is not directly a question of the individuals revalorisation.

Beyond the revalorisation #

First and foremost, my research can’t pretend to revalue the participation of human computers, keypunch operators or even today’s working women in computing as one single entity. This would mean reverting to an abstract model that makes disapear the differences between each status. As Valérie Schafer reminds us in Connecting Women ( Citation: 2015 Schafer, V. (2015). Connecting women: women, gender and ICT in Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth century. Springer. ) , social and political contexts are obviously very different in each case. We can’t get justice by blending status.

However, there are, I think, some common issues that come from science patterns: all women in these fields are paid less than men in the same profession, and there is a broad principle of devaluation of their work. Issues of their non-crediting and “invisibilization” are not the core of the problem: they are only symptoms of a deeper concern, that is the conception of knowledge emergence implying that thinking, producing informations is an abstract process.

I identify several potential drifts in the revaluation approach: first, the risk, as highlighted by Crystal Bennes in Klara and the Bomb ( Citation: 2023 Bennes, C. & Gallison, P. (2023). Klara and the bomb. The Eriskay Connection. ) , of producing an alternative history, and of creating a cast of exceptions. Like Sadie Plant, in her book Ones + Zero ( Citation: 1998 Plant, S. (1998). Zeros + ones: digital women + the new technoculture. Fourth Estate. ) , Bennes’ argument is that the production of a feminist history that replaces male figures with female ones will not impact the problem of the dominant history at the roots. There is also the risk of creating mythical figures as imposing as Father Busa. To say otherwise, we don’t need mothers, or authority figures of lone scholar, we need communities models. Besides, not all women who worked in the development of computer science were Ada Lovelace or Grace Murray Hopper, have had the same impact on the history of computer science and not all women were hidden by a system – some agreed with the system in place. Above all, such approach of thinking exposes us to the most insidious risk of all: glorification. Among the computers and operators, some of these women have contributed to destructive activities by providing data to test various bombs (like the ENIAC six).

Patsy Simmers, holding ENIAC board; Gail Taylor, holding EDVAC board; Milly Beck, holding ORDVAC board; and Norma Stec, holding BRLESC-I board. U.S. Army/ARL Technical Library Archives

[…] just because women were involved in this work, and that their work has been suppressed, it does not mean they should be celebrated as feminist heroes. The work these women did had serious and damaging consequences in the real world, and I cannot talk about them without talking about the appalling impact of their work. ( Citation: 2023 Bennes, C. & Gallison, P. (2023). Klara and the bomb. The Eriskay Connection. )

On a more concrete level, listing all the actors in the production of an article, would have the effect of what I would call a film credits: in cinemas, no one stays to look at the names of all the people, and only the name of the director as the unique and lone producer is kept in mind. To refer to McPherson, to add is not to include and since there is an epistemological model at the foundation of power and domination dynamics, it is unlikely that the issue will be resolved in a single generation time.

Many of the archival recovery efforts in the early years of DH deployed a similar additive logic, despite their good intentions. When these efforts focused on adding race or gender to digital archives and data sets, there was an implication that simply adding new data as content is all that is needed to get at some truth about race or gender. While it is hard to argue against, for example, including women authors in a database of nineteenth-century writers, such an approach is more additive than integrative or relationnal. ( Citation: McPherson, 2018 McPherson, T. (2018). Feminist in a software lab: difference + design. Harvard University Press. )

The issue is therefore not so much to reshape myths and represententions, as to challenge epistemological patterns. To redesign our critical knowledge in Digital Humanities, the petites mains model intends to analyse conditions of knowledge production and transmission in the Humanities to bypass a traditional model.

To conclude by an acknowledgement #

To conclude this paper, I would like to acknowledge a biased approach of mine that is very much centered on equality issues and very much informed by feminist readings. This is not to say that the petites mains are not the hands of other communities, and in particular of visible or invisible minorities. There is a large colonial and post-colonial angle to the petites mains culture that involves many other issues represented in particular by Casilli’s study of digital labor:

There is no artificial intelligence, only the work of someone else’s click. ( Citation: Casilli, 2021 Casilli, A. (2021). Il n’y a pas d’intelligence artificielle, il n’y a que le travail du clic de quelqu’un d’autre. (pp. 33). Editions du Détours. Retrieved from https://hal.science/hal-03560718 )

This is the reason why the topic of the transparency of the production processes is a core issue of our research that we must set to grasp. It is important to document our research project along the way, as McPherson reminds us in Feminist in Sowtware Lab ( Citation: 2018 McPherson, T. (2018). Feminist in a software lab: difference + design. Harvard University Press. ) , because it is not so much our job to conceive working tools that will change and save the world and culture, as it is to trace and witness working practices. These reality of our research are left by the logic of the archive in the abstraction and obscurity of science.

Bibliography #

- Bennes & Gallison (2023)

- Bennes, C. & Gallison, P. (2023). Klara and the bomb. The Eriskay Connection.

- Betti (2016)

- Betti, E. (2016). Gender and Precarious Labor in a Historical Perspective: Italian Women and Precarious Work between Fordism and Post-Fordism. International Labor and Working-Class History, 89. 64–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547915000356

- Cardon & Casilli (2015)

- Cardon, D. & Casilli, A. (2015). Qu’est-ce que le digital labor?. INA.

- Casilli (2019)

- Casilli, A. (2019). En attendant les robots: enquête sur le travail du clic. Éditions du Seuil.

- Casilli (2021)

- Casilli, A. (2021). Il n’y a pas d’intelligence artificielle, il n’y a que le travail du clic de quelqu’un d’autre. (pp. 33). Editions du Détours. Retrieved from https://hal.science/hal-03560718

- Collet (2004)

- Collet, I. (2004). La disparition des filles dans les études d’informatique : les conséquences d’un changement de représentation. Carrefours de l'education, n° 17(1). 42–56. Retrieved from https://www.cairn.info/revue-carrefours-de-l-education-2004-1-page-42.htm

- Collet (2017)

- Collet, I. (2017). Les informaticiennes : de la dominance de classe aux discriminations de sexe. 1024 – Bulletin de la société informatique de France(2). 25. Retrieved from https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:92679

- Jones (2016)

- Jones, S. (2016). Roberto Busa, S.J. and the emergence of humanities computing: the priest and the punched cards. Routledge.

- McPherson (2018)

- McPherson, T. (2018). Feminist in a software lab: difference + design. Harvard University Press.

- Mellet (2023)

- Mellet, M. (2023). Les petites mains de l’édition : réflexions pour des environnements éditoriaux équitables, pluriels et inclusifs. In Communication scientifique et science ouverte. (1, pp. 83–102). De Boeck Supérieur.

- Morley & Collet (2017)

- Morley, C. & Collet, I. (2017). Femmes et métiers de l’informatique : un monde pour elles aussi. Cahiers du Genre, 62(1). 183–202. https://doi.org/10.3917/cdge.062.0183

- Nyhan & Flinn (2016)

- Nyhan, J. & Flinn, A. (2016). Computation and the Humanities: Towards an Oral History of Digital Humanities. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20170-2

- Nyhan & Passarotti (2019)

- Nyhan, J. & Passarotti, M. (2019). One Origin of Digital Humanities: Fr Roberto Busa in His Own Words. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18313-4

- Plant (1998)

- Plant, S. (1998). Zeros + ones: digital women + the new technoculture. Fourth Estate.

- Rockwell (2013)

- Rockwell, G. (2013). Tasman: Literary Data Processing – Theoreti.ca. Retrieved from https://theoreti.ca/?p=4571

- Schafer (2015)

- Schafer, V. (2015). Connecting women: women, gender and ICT in Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth century. Springer.

- Terras (2013)

- Terras, M. (2013). For Ada Lovelace Day – Father Busa’s Female Punch Card Operatives. Melissa Terras. Retrieved from https://melissaterras.org/2013/10/15/for-ada-lovelace-day-father-busas-female-punch-card-operatives/

- Unsworth (2004)

- Unsworth, J. (2004). Forms of Attention: Digital Humanities Beyond Representation.. John Unsworth. Retrieved from https://johnunsworth.name/FOA/

- Villiers de L'Isle-Adam & Adams (2001)

- Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, A. & Adams, R. (2001). Tomorrow’s Eve (1st paperback ed). University of Illinois Press.

-

The term “amanuensis” for textual assistants could well apply, but it mainly concerns textual work environments, while the “petites mains” seems to be able to reach beyond. ↩︎

-

The french version: “L’arrivée des micro-ordinateurs a créé des sociétés de hackers […] presque exclusivement masculin[e]s et hostiles aux filles. […] Le hacker serait devenu l’idéal-type de l’informaticien. Ce métier, non seulement ne correspond plus à l’image que les filles ont d’elles-mêmes, mais leur semble même franchement hostile.” ↩︎

-

Between 1930 and 1950, the term “human computer” was used to designate women in particular, who did computing work. In her book My Mother was a Computer ( Citation: 2005 Hayles, N. (2005). My mother was a computer: digital subjects and literary texts. University of Chicago Press. ) , Hayles refers by title to Balsamo’s formula in his book Technologies of the Gendered Body ( Citation: 1996, p. 133 Balsamo, A. (1996). Technologies of the gendered body: reading cyborg women. Duke University Press. ) : Balsamo’s mother was a human computer, a fact recalled by Balsamo in order to understand how information technologies inform gender, and what are the gender implications of structures in the sciences of technology. ↩︎

-

In Understanding Media: the Extension of Men (1964), McLuhan writes: “Much of [transport] was by pack animal — woman being the first pack animal. […] Some writers have observed that man’s oldest beast of burden was woman, because the male had to be free to run interference for the woman, as ball-carrier, as it were.” ( Citation: 1964, p. 106 McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill. ) In McLuhan perspective of media, the woman, like a technical extension, allows the man to have his hands free. ↩︎

-

The Lord is in love with a woman of magnificent beauty, but whom he considers to be a complete imbecile. To enable him to love her completely, Edison replicates the woman’s appearance in a machine, giving her a literary culture. ↩︎

-

The “I blush if I could syndrom” was for more than 10 years the answer of Siri when insulted ( Citation: UNESCO & Coalition, 2019 UNESCO & Coalition, E. (2019). I’d blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education . UNESCO https://doi.org/10.54675/RAPC9356 ) . On this topic, I highly encourage you to follow Lai-Tze Fan and Hasti Atapour’s research (The Evolution of Siri’s Sexism and Apple’s Corporate Social Responsibility, CSDH 2023). ↩︎